Glossary

Reading and interpreting texts from the 17th and 18th century can be a challenge because of the use of words and spelling that differ from nowadays modern Dutch. Glossaries can be useful to researchers in understanding the meaning of specific words that occur in archival sources and originate from other languages. The Dutch archives at ANRI contain lots of words that come directly from languages spoken in the South-East Asia region, but also from other regions.

Few glossaries are digitized and available online to support reading old Dutch texts, like the VOC glossary (largely based on the published descriptions of the VOC by Pieter van Dam in 1693) and ship terms from the 17th century (published by Witsen in 1671). The book publication by P.G.J. Sterkenburg on 17th century Dutch language has not been digitized so far unfortunately.

When the Marginalia to the Daily Journals were digitized it became clear that these marginalia also contain lesser known terms originating from Malay, Javanese and other languages at the time of the Dutch presence in the 17th and 18th century. Mona Lohanda selected a few hundred terms from the marginalia and some bundles of Resolutieboeken to be explained further. She already made references to the VOC glossary and other sources. The terms are published here on this web page and can also be downloaded (see below). Dr. Tom Hoogervorst performed extensive additional research from an etymology point of view, meaning that the linguistic origin of terms has been analysed further. These results have been added to the glossary here as well. The glossary published here can be extended in future by studying for example the series of Resolutieboeken and Appendices, but it is already a very valuable source to the reading and understanding of old Dutch texts especially in the VOC archives of ANRI.

The following persons made this publication possible through their great effort and expertise:

- Dr. Mona Lohanda, Senior archivist at ANRI

- Dr. Tom Hoogervorst, Asian linguistic researcher at KITLV Leiden

- Mr. Marco Roling, Information engineer at The Corts Foundation

- Mrs. Nurhayu Santoso, Indonesian translator

Glossary based on the Dutch VOC records at ANRI

Download the Glossary here in PDF or CSV format:

Tracing the sources of VOC vocabulary

By Dr. Tom Hoogervorst (KITLV, University Leiden)

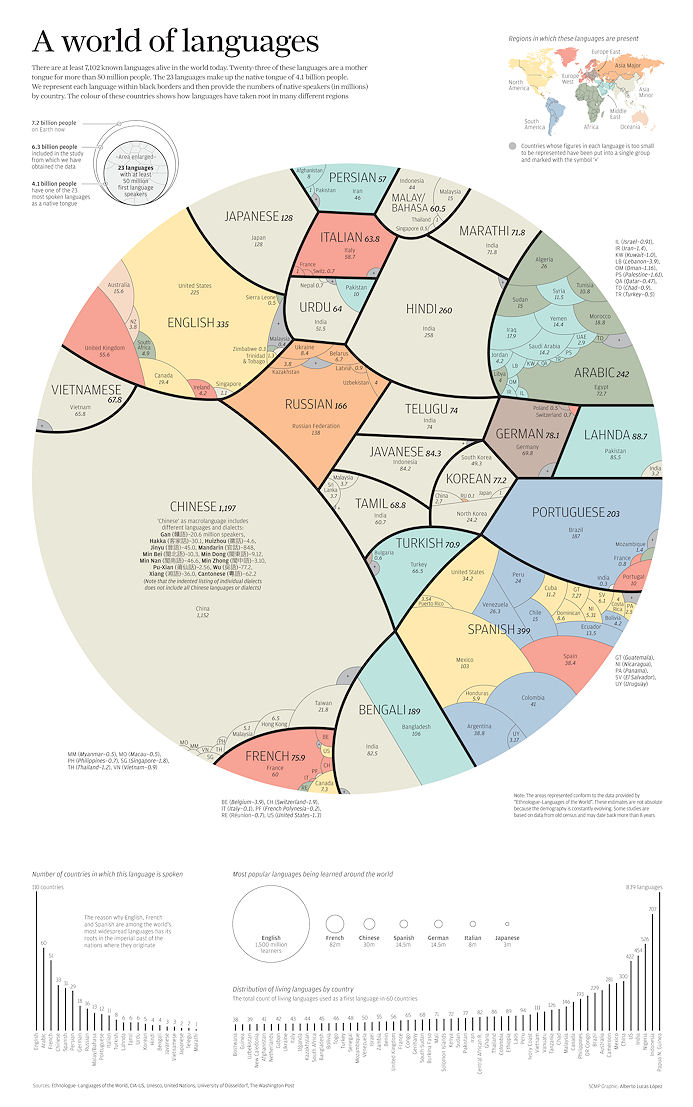

The considerable non-Dutch segment of the glossary, as presented here, represents a wide array of European and Asian languages. Some of these have influenced 17th-century Dutch directly, while others lent their vocabulary to regional contact languages – such as Persian, Hindi and Malay – with which the Dutch had been in contact. A distinction can be made between foreign loanwords that predate the establishment of the Dutch in South-East Asia (e.g. from Italian) and those acquired as a result of maritime voyages (e.g. from Javanese).

The considerable non-Dutch segment of the glossary, as presented here, represents a wide array of European and Asian languages. Some of these have influenced 17th-century Dutch directly, while others lent their vocabulary to regional contact languages – such as Persian, Hindi and Malay – with which the Dutch had been in contact. A distinction can be made between foreign loanwords that predate the establishment of the Dutch in South-East Asia (e.g. from Italian) and those acquired as a result of maritime voyages (e.g. from Javanese).

Dutch was already a cosmopolitan language prior to direct contact with the peoples of coastal Asia. Iberians had preceded the Dutch in the Atlantic, the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea. The Portuguese were the first Europeans to leave a deep impact on the commercial, political, cultural, technological and military systems of Africa and Asia. At the same time, they introduced several concepts they encountered on their eastward voyages into Europe. Meanwhile, several novelties from the Americas entered European languages (Dutch, English, French, etc.) through the Spaniards. Italian and Latin had left their imprint on the cultural vocabulary of the Low Lands even earlier.

Geographically positioned between Europe and Asia, the Arabs had played a key role in connecting the two continents since classical times. Several Arabic loanwords entered Europe directly through the Iberian Peninsula, or indirectly through Persian, Hindi, Malay and other Asian languages. In the arena of commercial terms, the Yemen dialect was especially influential. Persian was the cultural language of Iran, Central Asia and the Indian Subcontinent when the Dutch made their first incursions into the Indian Ocean World. Turkic peoples from Central Asia – who spoke the now extinct Chagatai language – also left an important lexical imprint on Persian and the languages of India.

In the Indian Subcontinent, Sanskrit had long ceased to be a mother tongue, yet remained a language of liturgy. Hindi, also known as Urdu or Hindustani, was the major vernacular language in North India. On India’s west coast, Gujarati, Marathi and Malayalam were among the first South Asian languages Europeans encountered, so many Indian concepts entered Europe through these sources. Further east, Tamil was spoken along the Coromandel Coast and the northern parts of the island Sri Lanka, where Sinhala constituted the major language.

In Maritime Southeast Asia, the major lingua franca since pre-modern times was Malay. Given the importance of the Spice Islands, several VOC terms can be identified specifically with the Malay dialect of Ambon. Ternate and Tidore, the closely related languages of two competing sultanates of eastern Indonesia, also impacted on the vocabularies of the region. Other influential languages of the Indonesian archipelago were Javanese, Bugis and Makasar. The first Chinese languages in contact with Dutch, Portuguese and English were Cantonese and especially Hokkien (Southern Min), whose speakers had been in close contact with Southeast Asia prior to the arrival of Europeans in the region. The Japanese language also exchanged numerous words and concepts with Portuguese and later Dutch.

Sources used

- Arabic – Wehr, Hans, 1976. A dictionary of modern written Arabic. Ithaca, New York: Spoken language services. Third edition.

- Burmese – Myanmar, 1993. Myanmar-English dictionary. Kensington: Dunwoody Press. Republication. Accessed through here >>

- Chagatai – Vámbéry, Hermann, 1867. Ćagataische Sprachstudien. Leipzig: F.A. Brockhaus.

- Hindi – Platts, John T., 1884. A dictionary of Urdu, classical Hindi, and English. London: W. H. Allen & Co. Accessed through here >>

- Hokkien – Douglas, Carstairs, 1899. Chinese-English dictionary of the vernacular or spoken language of Amoy, with the principal variations of the Chang-chew and Chin-chew dialects. London: Publishing office of the Presbyterian Church of England. New edition.

- Malay – Wilkinson, R.J., 1932. A Malay-English dictionary (romanised). Mytilene: Salavopoulos and Kinderlis. Two volumes.

- Malayalam – Gundert, H., 1962. A Malayalam and English dictionary. Kottayam: Sahitya Pravarthaka. Second edition.

- Marathi – Molesworth, James Thomas, 1857. A dictionary, Marathi and English. Bombay: Bombay Education Society's press. Second edition. Accessed through here >>

- Persian – Steingass, Francis Joseph, 1892. A comprehensive Persian-English dictionary, including the Arabic words and phrases to be met with in Persian literature. London: Routledge & K. Paul. Accessed through here >>

- Portuguese – Dalgado, Sebastião Rodolfo, 1921. Glossário Luso-Asiático. Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade.

- Sinhala – Clough, B., 1892. Siṅhalese-English dictionary. Colombo: Wesleyan Mission Press, Kollupitiya.

- Tamil – Tamil, 1924-36. Tamil Lexicon. [Madras:] University of Madras. Six volumes. Accessed through here >>

- Ternate – Atjo, Rusli Andi, 1997. Kamus Ternate-Indonesia. Jakarta: Cikoro Trirasuandar.

- Yemen Arabic – Piamenta, Moshe, 1990-1991. Dictionary of post-classical Yemeni Arabic. Leiden etc.: Brill.

Download the infographics in its original format here >>>